Some months ago, a friend of mine gave me an article from Endnotes. It explains a weird and controversial feature of capitalist economic systems in a way I found very convincing. But its scope is much larger than what I need it for here, so I’ll try to give the best summary I can.

The starting point is two related dynamics at the heart of capitalist economies.

The first dynamic is borne of the fact that developed capitalist systems rely on the existence of ‘distance,’ so to speak, between people and the goods and services they need to survive. This distance has been established through a centuries-long process of removing people’s direct access to the means of their subsistence, the dual ends of which are increasingly efficient production and the creation of a mass of wage-earners who comprise the market for products.

The result of is a sort of permanent crisis experienced by working people: because they do not have direct access to the means of their subsistence, they must obtain wages to purchase the goods and services they need for life. People are therefore bound to the job market, and capitalist firms depend on them spending their wages on the products they produce.

Marx explains this with perhaps more art, and certainly more vigor than I do:

“[Capital] takes good care to prevent the workers, those instruments of production who are possessed of consciousness, from running away, by constantly removing their product from one pole to the other, on the one hand, the means for the workers’ maintenance and reproduction; on the other hand, by the constant annihilation of the means of subsistence, it provides for their continued re-appearance on the labor-market. The Roman slave was bound by chains; the wage-laborer is bound to his owner by invisible threads.”

Capital, Volume I, Chapter 23, p. 719

The second dynamic results from the fact that just as workers compete for wages, capital competes for profits. It must move perpetually across firms, across sectors, to find its most profitable use, or it will fall behind other smarter and faster capital. The perpetual movement of capital causes firms to rise and fall, drives labor-saving innovation, and spreads these innovations across sectors. And the threat of capital leaving, as it must, when profitability falls, leads firms invariably with two choices to re-establish their profits: “the slaughtering of capital values” (i.e. selling capital investments for less than their previous value) and “the setting free of labor” (i.e. firing people). All capital must accumulate, it must do it faster than other capitals, and when things aren’t working out, measures must be taken to quickly re-establish a competitive rate of profitability.

These two dynamics make up the “valorization process,” or how capitalist economies continue to create accruing value. The key observation of the Endnotes article is how the perpetual nature of this process affects economies (and the societies they serve) in the long run. We’ve got to get a little deeper in the weeds here so forgive me for that.

Every industry—from airlines to car manufacturing to tobacco—‘matures’ over time. When a product first becomes available, prices are quite high and the product is purchased only by the wealthy. Over time, labor-saving innovations are introduced, first in one place then another, expanding the market for the product as the price falls. When this is done right (and the law of profit maximization ensures that it is) costs fall much faster than prices do, and firms experience a period of high profitability. Suddenly, everybody and their mother (in the world of competitive capital) wants in. New firms are created, with jobs and the latest tech and lots of gusto. But the market soon becomes saturated, prices fall more quickly than costs, and profitability falls. Capital will leave for greener pastures, workers will be fired. Ideally, they are available to be taken up by other industries—maybe they can have some job retraining.

These workers on the margins, available to be hired into profitable industries, able to be fired when profitability falls, are absolutely necessary for this cycle to be possible, a cycle at the center of capitalist systems. And such systems will continue to separate workers from the means of their subsistence, or remove them from unprofitable wage-earning jobs, to achieve the available marginal workforce they need.

“Expansion…is impossible without disposable human material, without an increase in the number of workers which must occur independently of the absolute growth of the population. This increase is affected by the simple process that constantly ‘sets free’ a part of the working class; by methods which lessen the number of workers employed in proportion to increased production. Modern industry’s whole form of motion therefore depends on the constant transformation of a part of the working population into unemployed or semi-employed ‘hands.’”

Capital, Volume I, Ch 25, §3, p. 786

Despite the fact that I’m quoting Marx here, this is a commonly-accepted feature of capitalism. Schumpeter described this cyclical shedding of capital and labor, followed by reinvestment and re-hiring, as ‘creative destruction’: for the West Wing fans out there, think the communication workers union.

What’s not mainstream, however, is the implication Marx drew from this. He called these unemployed, semi-employed, under-employed workers the “Industrial Reserve Army,” and argued that their ranks in capitalist systems would necessarily expand over time, irrespective of population growth:

“The greater the social wealth, the functioning of capital, the extent and energy of its growth, and therefore also the greater the absolute mass of the proletariat and the productivity of its labor, the greater is the industrial reserve army. The same causes which develop the expansive power of capital also develop the labor-power at its disposal. The relative mass of the industrial reserve army thus increases with the potential energy of wealth. But the greater this reserve army in proportion to the active labor-army, the greater is the mass of a consolidated surplus population…[.] The more extensive, finally, the pauperized sections of the working class and the industrial reserve army, the greater is the official pauperism. This is the absolute general law of capitalist accumulation.”

Capital, Volume I, Ch. 25, §4, p. 798.

Let me break this down here. Marx is arguing that as the wealth of a capitalist economy grows, the proportion of workers who exist on the margin of the economy grows with it. These are people who do not have job security, but who are hired when new industry, underdeveloped and thus labor-intensive, requires them, and thrown off as soon as the dictates of profitability suggest. There’s more to it though: Marx is also saying that there will grow within this group a hard core of people who are entirely superfluous to the economy. Perhaps they provide consumption with whatever money they can scrounge up, but the economy does not need their labor: they are absolutely redundant, a surplus population.

As the Endnotes piece points out, it’s not immediately clear that this follows. But Marx offers two observations in his support. First, that as the amount of capital in an economy grows, so does competition over profits, and accumulation must therefore become even more rapid to attract investment. In such an environment, capitalists will rightly prefer to invest in more mutable technology and economize on stubborn and immobile labor. Second, that new industries will not pick up the hiring slack, because they too will be affected (in their competition to attract investment) by the shift in preference from labor-intensive to capital-intensive models. Thus, new capital-infused industries will attract fewer and fewer workers, and old industries, cyclically and periodically reproduced in new compositions, will with each iteration employ fewer and fewer workers.

These related dynamics are the reason why labor-saving technologies generalize both within and across industries, and this generalization is irreversible. Why should companies give up labor-saving innovations when their profitability is restored? Indeed, such innovations were likely the precondition for its restoration!

And they also explain how in capitalist economies, without intervention, the relative decline in labor demand threatens to outpace the capital accumulation that drives it.

Of course, the level of intervention in developed economies has been significant to this point. Huge amounts of deficit financed economic support for high-employment industries has been the sine qua non of modern full employment, as has the fantastic growth of the service sector. But the problems here seem obvious.

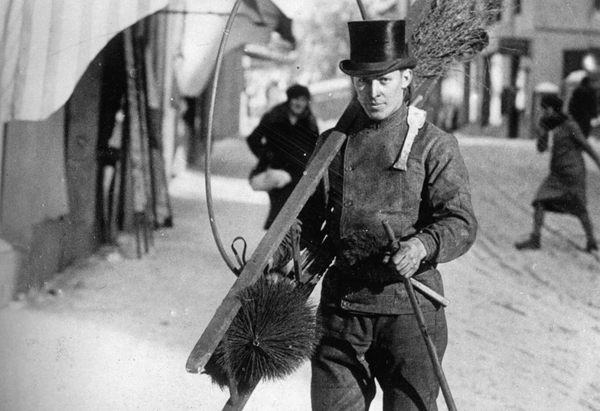

First, the heavy-duty industries that absorbed both capital and labor through the middle of the 20th century—think automobiles, freight and passenger rail, manufacturing—have experienced for decades absolute declines in employment, their financial pre-eminence replaced by nimble, high-market-cap-low-payroll technology(capital)-intensive firms. And second, service industries, which pick up lots of the labor ‘slack,’ are not themselves productive; they are highly reliant on consumers having the money to spend on them in the first place, and they are stubbornly low growth with limited opportunities for increasing profitability. Indeed, those service occupations still around are those which have proved stubbornly ill-suited to replacement by products. Dishwashers, the consumer good, used to be a guy named Jeremy who washed dishes; the chimney sweep was replaced by central heating.

There was a time when labor-saving innovations were thought to herald new eras of leisure and self-improvement for the masses. But in a society based on wage-labor, as all capitalist economies are, it is possible that “the reduction of socially-necessary labor-time—which makes goods so abundant—can only express itself in a scarcity of jobs, in a multiplication of forms of precarious employment.”

Okay, that’s enough of the economic theory. I want to tell you why I made you read all that.

I work in the criminal legal system, and many of my colleagues style themselves abolitionists. And so we do things like read abolitionist writings, go to workshops, put taglines in our emails like “free them all.”

One of the things many abolitionists, a group of which I count myself a member, talk about in their books, workshops, and such is their distrust for reforms. Prison was called a reform, we say, and look where that got us. And prison was a reform, a ‘humane’ alternative to stocks, whippings, bondage, and executions. The trouble is that today, our prisons are filled to the brim with people who will spend significant portions of their lives there, locked in a cage. How did they get there? Why does this seem to be a modern problem? Our current prison population far exceeds the masses of innocents who passed through Stalin’s gulags, and yet we seem unable to stop locking people up.

Perhaps it’s something in the way our society works. And I don’t just mean our country’s intractable struggle with racism, the drug war, gun ownership, or abnormally high rates of run of the mill violence. I mean our economy: how we accumulate resources and distribute them.

Right now, in February of 2023, we’re experiencing the tightest labor market in decades, hot on the heels of the largest bonanza of social spending in history. And yet everyone can observe, especially in the criminal legal world, that the number of people living on the streets, stealing food or selling contraband to survive, hopelessly addicted to soul-crushing drugs, seems higher than any time in recent memory.

My perspective is undoubtedly biased: I work in indigent defense, and so many of my clients are unable to afford many things, not just attorneys. But so many of the people I encounter in this circumstance seem barely to have had a chance to thrive at all. Many of them grew up on social support. Even those with education, even those that had jobs, were unable to earn a decent living. And our country broke them down, one thing at a time, or agents of the state caught them in one of the precious few moments of weakness they could ever afford.

And when they go to Rikers, or the Tombs, or some upstate prison to live in a cage, the state pays more to lock them up than it ever offered them free. New York City spends $556,539 to incarcerate one person for a full year, or $1,525 per day. I’m fairly certain that every single person convicted of every crime within the five boroughs would take 10% of that figure not to have done what they allegedly did. Many would take it back for free. Give each of them half of that amount, and you would never see them in a courtroom again.

But we can’t, and we don’t. Why? Because our society can’t exist without pushing people to the margins, without making them take crappy jobs and even crappier wages to survive. Sometimes even those jobs aren’t there for them, because the economy we built doesn’t need them, or have a place for them in the first place. Our society offers absolutely nothing to so many people, a number that grows every day. And prisons, once a reform, perhaps now serve to vacuum these people up. They take them off the streets so we need not feel what we’ve done to our brothers and sisters. So we don’t have to look the brutality of our system in the eye.

If this theory of surplus populations is right—this idea that capitalism detaches all of us from the means of our survival, and makes more and more of us unnecessary with each passing day—then the problem of abolition is only growing. It means that we will face greater pressure, with each passing year, to do something with the people the capitalist system no longer needs. And prison is far too popular an answer.