This article is the third and final of a multi-part series about the West Virginia Mine Wars. The first article can be found here, and the second here. Much of this research and writing was part of some academic work, though many of my favorite details had to be cut to meet those pesky word-counts. Nevertheless, I wanted the opportunity to tell as much of the story of the Mine Wars as I could, an event that has somehow been scrubbed from American history. It is a tale of tragedies and triumphs, shocking cruelty and vicious exploitation, stamped-out revolution and deep solidarity in the American working class. I hope you enjoy it.

I. Why I Wrote about the Mine Wars

I want to talk about revolution—more specifically, American revolution. The study of revolution has always been ‘a lively and disorderly field,’ but I believe the subject and substance of this article will be somewhat unprecedented.[1] That is because while I propose to discuss a failed revolution in a country whose failure to (re)produce revolutionary activity has spawned a cottage industry of scholarship,[2] the events of the West Virginia Mine Wars have almost totally escaped academic notice, and certainly no scholar of revolution has seen fit to study them. The purpose of this third and final installment is therefore twofold: to begin tugging on this unmolested strand of the American historical fabric, and to demonstrate that it will, with further study, assist efforts to unravel the age-old puzzle of how we might get around to revolution in the United States.

Because I am convinced that “[no] study of revolutions [can] usefully be separated from that of the specific historical periods in which they occur,”[3] I have already exerted considerable effort to present a narrative of the events in question with as much detail as the medium of little-read blog posts allows. You can find parts one and two, the story of the Mine Wars, here and here. But the time has come for the study of revolution to play a starring role. That is because I hope to show that the West Virginia Mine Wars were not only actual instances of revolutionary collective action in American history, but an expository episode of the durability of the American federal system, the true nature of class formation and class interests, and the extraordinary unchecked power of organized capital and the independent judiciary in the United States.

I will begin, therefore, with a critical discussion of the leading literature on revolutions, identifying a structural perspective of analysis (with some modifications) as the most persuasive treatment to date. The framework I develop will then serve as a lens of analysis for the events of the Mine Wars, allowing us to draw out insights as well as tentative arguments about how the American system has responded to revolutionary collective action and the challenges it poses to radical movements.

Finally, I hope in the following pages to offer critical suggestions towards a particularly American theory of revolution. “All forms of political organization have a bias in favor of the exploitation of some kinds of conflict and the suppression of others[:] some issues are organized into politics while others are organized out.”[4] The American system is no different, and so the application of general explanatory theories of revolution will undoubtedly bring into high relief the mechanisms by which the United States has sustained the challenges of collectivities it ‘organized out.’

II. Some Literature

The first task of revolution scholarship is always to define what qualifies a collective action as revolutionary. Scholars of revolution have naturally focused on groundbreaking and influential events about which we know the most, and so the ‘great revolutions’ have de facto formed the starting points for analyzing the rest.[5] But the number of attempted coups, insurrections, civil upheavals, and temporary ‘revolutions’ across history surely dwarfs that of the bona fide, paradigm-shifting “social revolutions.”[6] Thus, we are confined to a literature which has lavished more attention on the internal workings of the eighteenth-century Jacobins than the 115 successful revolutions of nineteenth-century Latin America,[7]creating a bias towards the methods and mechanisms of successful (and lucky) revolutionaries operating in world-historical powers. The miners of West Virginia were neither lucky nor successful, and their nation only recently formidable.

One influential scholar defends their focus on large and successful sociopolitical transformations on the basis that “successful social revolutions probably emerge from different macro-structural contexts” than those that fail.[8] But this perspective belies the fundamental observation that revolutions are periods beyond the control of any one actor: individual choices matter, but during revolutions all planned action takes place under the influence of uncontrollable forces.[9] Thus the most effective strategist will always fail if conditions are not ripe for her success, but this doesn’t mean her movement is irrelevant to the study of revolution.[10]

Still, our brilliant strategist is not a revolutionary if she never leaves her basement. There must be a thing that happensthat is in fact a revolution, and I adopt Tilly’s definition that a revolution is a special case of collective action that alters circumstances such that individuals can choose between allegiance to the current sovereign or the insurgent claimants to power.[11] Thus, the emergence of a period of “multiple sovereignty” is the sine qua non of the historical fact of revolution.[12] Skocpol takes issue with this reduction because “it strongly suggests that societal order rests, either mentally or proximately, upon a consensus of the majority (or of the lower classes) that their needs are being met,” and while I agree that no such condition for social order exists, I am referring to a situation in which individuals believe it is now viable to substantively reject the sovereignty of the old order, regardless of whether they view it as legitimate. From this starting point we can begin to survey the field.

There are five major groupings of the so-called ‘general’ theories of revolution. The first and most influential grouping is Marxist, the basic principles of which have become so influential that any theorist must either work within them or explain why not. Marx viewed revolutions as class-based movements spurred by disjunction between the social relationsof production—how labor is divided, how property is protected, how far-removed people are from the products of their work—and the material productive forces of society—the physical instruments, resources, and labor power used for production.[13] This disjuncture is expressed by increasingly intense class-conflicts during which a new mode of production—the combination of social relations and material forces of production—supports the struggle of each proto-revolutionary class against the dominant class, as capitalism supported the bourgeoisie’s struggle against feudal aristocrats.[14] Revolutions are accomplished by a self-consciously revolutionary class (sometimes with allies), and are completed when the new mode of production and revolutionary class are dominant.[15]

Ted Gurr’s aggregate-psychological theory of revolution—the second grouping—hypothesizes that revolutionary psychology is driven by “a perceived discrepancy between men’s value expectations and their value capabilities,” by which he means an individual’s recognition that his society lacks the tools for him to attain the goods and conditions he expects for himself.[16] The greater the gap between capacity and his expectations, the greater his motivation to engage in revolutionary violence.[17] I believe we must look elsewhere to understand revolutions, as even the most discontented mass of people cannot achieve revolutionary change without minimal levels of organization and resources, and even then, particularly repressive tactics can make revolutionary action far too costly.[18]

Chalmers Johnson, the expositor of the systems/value-consensus theory and third grouping, argues that revolution occurs at a particular stage in a social system’s attempts to accommodate “actual, or incipient, metastasis of social ills” that cause a “loss of confidence” in the government or a “loss of consensus.”[19] If a social system is unable to adjust and relieve its dysfunction, either “the old order simply wheezes to a stop and a new system is formed on the basis of virtually unanimous agreement,” or social subjects will resort to violence to relieve dysfunction, Johnson’s definition of revolution.[20] And these processes may be accelerated by external factors—war, economic collapse, environmental disaster, the like—such that despite an old order’s best efforts a revolution is all but inevitable.[21] Johnson’s theory of revolution falters on the same point as Gurr’s: the idea that loss of legitimacy for the pre-revolutionary regime is the essential condition for revolution. It is not. Indeed, it is not clear that popular legitimacy is a necessary condition for the sustainability of any social order, much less those which have resisted revolution.[22] Moreover, I am not convinced that violence is a core aspect of revolution, rather than a simple by-product of the competition for newly-unleashed resources and coercive means that most every revolution produces.[23]

The contributions of Marxist theory discussed above join political conflict/opportunity theories,[24] which focus on the organizational capacities and opportunities available to groups competing for power, and structural theories, which view revolutions as non-voluntarist ‘snowballs’ of collective action within the right series of structural conditions, to form the body of theory I apply here.

Beyond the definitions, the first principle of revolutions is that they require both organizational resources and the right opportunity. No matter their companion’s measure, each is necessary.[25] The need for organizational resources flows from the observation that “revolutions and collective violence tend to flow directly out of a population’s central political process, instead of expressing diffuse strains and discontents.”[26] Revolutions are political events, and challenger collectivities are admitted to the political cognizance of a population by demonstrating their capacity to mobilize significant numbers of individuals and quantities of resources. A population’s “central political process” is not only its actual form of government or political institutions, but commonly recognized and structurally constrained methods of articulating political power as well. An 18th century French revolutionary movement had to put together a good public demonstration,[27] while twentieth century Russian revolutionary groups demonstrated their importance with high profile political assassinations, among other things.[28]

Just as essential to revolution is the right opportunity, a concept described variably as “revolutionary situations” or “epochs of social revolution.”[29] The necessity of revolutionary situations is demonstrated by the simple fact “that historically no successful social revolution has ever been ‘made’ by a mass-mobilizing, avowedly revolutionary movement.”[30] True enough, so-called vanguard parties lying-in-wait have been indispensable elements of many of history’s great revolutions, but “in no sense did such vanguards […] ever create the revolutionary crises they exploited.”[31] Put succinctly, “[r]evolutions are not made; they come.”[32]

And yet there is no ‘tell-tale’ sign of impending revolution, only cognizable markers of revolutionary potential. Lenin described revolutionary situations as a combination of divisive crises within the ruling class, growing discontent of the lower classes, and “a considerable increase in the activity of the masses.”[33] Skocpol describes revolutionary situations as highly contingent, a circumstance of crisis in the old regime with variable, context-based causes determined by intra- and inter-national institutional and world-historical developments.[34] McAdam, describing perhaps less-than-revolutionary “political opportunities,” flags “any event or broad social process that serves to undermine the calculations and assumptions on which the political establishment is structured…”[35] Each of these descriptions carries a discomfiting element of tautology, identifying some kind of crisis in the old regime and then working backwards to describe its complex yet allegedly-predictable causes.

To achieve a more reliable definition, I prefer to focus on the specific nature of the crisis in the old regime from a structural perspective. Any structure, governments included, “cannot function without the routinized exercise of structural power.”[36] Employees obey their bosses, tenants pay their landlords, the constable obeys the sheriff and the sheriff obeys the governor. But when these routine power-relationships break down, the very system they comprise is in grave danger. The implications of this observation are twofold. First, that a revolutionary situation, whatever its causes, exists when the old regime’s “routinized exercise of structural power” becomes sporadic or fails entirely. Second, that no regime, no matter how well-loved or well-armed, is immune to revolutionary potential. “Any system contains within itself the possibility of a power strong enough to alter it.”[37]

There are three remaining principles of revolution that are essential to elaborate. The first is that revolutions are best-understood as class-based movements, a crucial factor which distinguishes them from coups, outside agitation, or internal collapse in the face of war or economic ruin. I differ from many scholars of revolution, however, in my rejection of the Marxist conception of class relations, and by extension class interests, as “rooted in the control of productive property and the appropriation of economic surpluses from direct producers by nonproducers.”[38] Indeed I emphasize for the current purposes only two underlying principles of Marxist thought as it regards class and revolution: that the potential for class formation is often determined by shared positioning relative to the means of production, and that revolutionary strategy flows from recognition of the “latent political leverage available to most segments of the population.”[39]

Properly understood, “the interests of a class most directly refer to standing and rank, to status and security[:] they are primarily not economic but social.”[40] And by this I mean to say that material conditions must be a contextual, and never a fundamental feature of analyzing class formation and class interests. Human society is by nature reliant on economic factors, but “the motives of human individuals are only exceptionally determined by the needs of material want-satisfaction.”[41]So too is class-formation, in my view, the product of shared constellations of concrete daily experiences and mutually developed culture, rather than the material conditions that individuals experience.[42] The Marxist emphasis on exploitation as the basic point around which classes rally and articulate their interests carries an unduly economistic prejudice, obscuring the more-fundamental importance of social institutions, culture, status and dignity. It is around these points that we should expect classes to coalesce, and it is the degradation or deprivation of these bases of social-communal self-respect that we should expect to inspire revolutionary collective action. This adjustment would close two gaps in the Marxist literature on revolutions, explaining why destitution is more rarely a breeding ground for revolution than subsistence-or-better living standards,[43] and explaining the motivations of (oftentimes working-class) conservative revolutionary activity.[44]

The second principle is that the state should always be viewed as at least potentially autonomous, rather than a simple arena for social and economic disputes or a front for protecting the interests of the ruling class. A dispassionate look at what a state actually is may be instructive here. States are organizations that extract resources from society and deploy them to maintain coercive forces and administrative apparatuses; they also work to maintain their status as an organization so capable by preserving order and the integrity of their territory.[45] There is no reason to believe that such an organization is always beholden to the interests of its most powerful subjects because 1) the ruling classes are also in the business of extracting resources from society, in competition with the state, and 2) it is sometimes necessary for the state to wrest concessions from the ruling classes to maintain social order or territorial integrity.[46] Indeed when the subject of discussion is revolution, there is already reason to believe the state is in conflict with sectional interests of the ruling classes and struggling to maintain order.

Lastly, revolutions as non-voluntarist events; more specifically, we should never interpret the causes, processes, and outcomes of a revolution solely through the actions, intentions, and interests of the key groups involved. We have already discussed the non-correlation between a loss of ‘legitimacy’ and revolutionary agitation, as well as the fact that all revolutions take place under the influence of uncontrollable, sometimes world-historical forces. It need only be added that revolutions are extraordinarily complex events involving far greater numbers of individuals than those at the apparent center. “In fact, revolutionary movements rarely begin with a revolutionary intention; this only develops in the course of the struggle itself.”[47] Thus, while the key players in any revolution are undoubtedly important, observers (and participants) must always be aware that the advent of a revolutionary situation changes the circumstances of everyonewhere it exists. (Some people become revolutionaries simply because the insurgents now pay their salaries!)[48] And all of those involved make choices under the influence of intra- and inter-national economic, environmental, sociopolitical, or technological change, little of which many are aware. To use a phrase of Hobsbawm’s, “the evident importance of the actors in the drama does not mean that they are also dramatist, producer and stage designer.”[49]

In summary, the definition of revolution is a special case of collective action which results in the emergence of a period of “multiple sovereignty” when individuals can viably choose between allegiance to insurgent challengers and the old regime. An actual revolution is distinguished from other lapses in sovereign control by its necessary combination of a challenger group with organizational capacity/resources and the existence of a breakdown in the routinized exercise of structural power. Revolutions are class-based movements always, and the processes of class-formation and development of class interests are rooted in shared constellations of concrete daily experiences and social-communal bases of self-respect. In seeking the sources of revolutionary inspiration, we should look therefore to the degradation of the social institutions, culture, status, and dignity of challenger collectivities, rather than their material interests. We should also view the state as at least potentially autonomous from the interests of the ruling classes, especially where those interests compete with the state’s extraction of resources from society or efforts to maintain social order. And finally, revolutions are non-voluntarist events involving overarching circumstances and far-greater numbers of individuals than those who comprise the “key groups competing for power.

Now, if you haven’t yet parts one and two of this series, I suggest you do so now—the final paragraphs won’t make sense if you don’t. But before you do so, I wish to flag three questions implied by the revolution theories that will guide our analysis:

1) How does the American federal system condition the relationship between the state and the ruling class in revolutionary situations?

2) What is the nature of class formation in American revolutionary situations, and what types of class interests do revolutionary subjects articulate?

3) What mechanisms of the American system does the ruling class rely on in revolutionary situations, and how can revolutionary subjects effectively respond?

Once you get back to this page, we’ll analyze the historical record within this framework, seeking to establish comparative insights between the behavior of American revolutionaries within the American system and the revolution literature writ-large, as well as starting points for theory of revolution particular to the American system. One case study cannot answer such important questions with certainty, but I intend to make a start.

III. Analyzing the Mine Wars

Okay, so you’ve read or re-read the story of the Mine Wars, right?

If you have, we can quickly see that the events of the Mine Wars fit quite neatly into the principles of revolution we previously discussed.

First, the Mine Wars clearly resulted in extended periods of multiple sovereignty. Not only did huge quantities of miners form separate and insular communities during the strikes, but the repeated suspension of civil authority by state and federal officials created long periods of completely arbitrary law and order enforced differently by different parties to the conflict. Second, the striking miners possessed both organizational capacities and resources—the UMWA spent millions of dollars supporting their efforts[50]—and an opportunity in which routinized exercises of structural power were breaking down not just in West Virginia, but across the country. Third, the miners were members of self-consciously class-based movement making claims against ruling-class owners of the companies which employed them. Fourth, the mine operators received significant but by no means total support from the state apparatus. And finally, thousands of residents of southern West Virginia, and indeed the nation writ-large, became involved in the Mine Wars despite having no direct relationship with the conflict, and it is doubtful that any union official expected the extent to which the social order would collapse under the pressure of the strikes they called. But the Mine Wars have greater implications for the behavior of the American system under revolutionary stress too.

- How does the American federal system condition the relationship between the state and the ruling class in revolutionary situations?

At every turn throughout the Mine Wars, coal operators and allied capitalists in West Virginia appealed to State, and not federal, officials to enforce their claims against the striking miners. As it relates to our principle of the potentially-autonomous state, this fact elucidates a key difference between state and federal governments in the American constitutional system. The federal government is always and everywhere in competition against the ruling class over the resources extracted from society.[51] This was especially the case with bituminous coal in the early twentieth century, a resource which had enormous implications for the rest of the productive economy and was highly concentrated in the mountains of West Virginia.

State governments, on the other hand, acquire relative power in the constitutional system by competition over capital investment with other states, getting ahead by offering preferable environments for capital and protecting the interests of its owners when threatened. Indeed the West Virginia state government was eager to abdicate its role in maintaining social order, refusing to quickly reconstitute its National Guard in the face of a large insurrection, and favored conditions of martial law which reduced the capacity of the miners to resist the excesses of coal operators in civil forums. In fact, repeated declarations of martial law allowed the state to enlist in combat individuals local to Kanawha, Mingo, and Logan counties whose interests directly opposed those of the miners, imbuing the operators’ forces with a powerful class component which rivaled that of the miners.

A State government also has no interest comparable to that of the federal government in maintaining the integrity of its territory—indeed the federal government guarantees its boundaries. The federal government’s interventions reflected a more evenhanded balance between the miners’ and operators’ interests, a fact the miners themselves recognized, and more-carefully defused the violence with the likely stability of the entire nation in mind. The allegiances of local officials, on the other hand, proved to be a mixed bag. Some, like the Kanawha County sheriff who executed the infamous armored train raid on Holly Grove, were easily swayed by the financial inducements of the mine operators, while others, like Sheriff Sid Hatfield and the other unionist Democrats elected in the interwar period, remained staunchly loyal to their communities.

- What is the nature of class formation in American revolutionary situations, and what types of class interests do revolutionary subjects articulate?

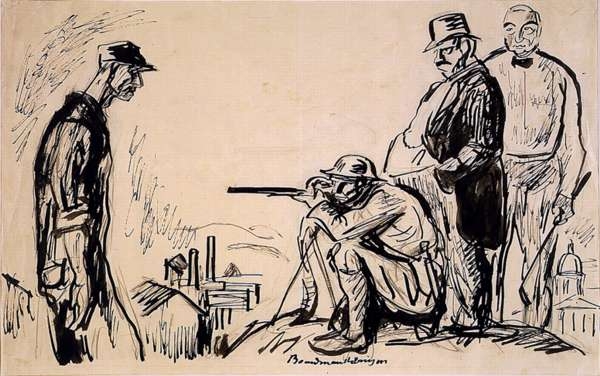

The processes of class formation which took place during the Mine Wars are challenging to both the Marxist perspective and the perspective I advocate above: extensive ethnographies are probably necessary for a satisfactory answer, but some insights are still possible. First, it is of note that while the miners were extraordinarily culturally diverse, they were bound together by constellations of concrete daily experiences entirely unique to their profession. Each day they travelled hundreds of feet below the surface to work in a dangerous environment, utilized techniques and forms of communication passed down through generations of experience, and adhered to strict moral codes of conduct in the division of labor and wages. Furthermore, miners and families across southern West Virginia suffered identical types of indignities at the hands of company men: check-weight and docking fraud, inflated prices at company stores, eviction and blacklisting, corporal punishment, sexual exploitation, and debt peonage, among others. It was these experiences, and not their simple poverty, that formed UMWA members and non-members, wives and daughters, into the revolutionary class which endured enormous hardship to press their claims against the mine operators.

An examination of the sorts of claims over which miners were willing to sustain violence are also instructive. In neither of the Mine Wars did UMWA members resort to violence over the operators’ refusal to grant wage increases—even when the Lever Act federally guaranteed a specific wage increase, Frank Keeney and District 17 leadership pressed their claims through complaint procedures and lobbying of public officials. Rather, the issues over which the miners resisted violently were demands for fair, unarbitrary payment procedures, basic liberties of American citizens, justice delivered at the hands of accountable officials, and the operators’ attempts to destroy unionism among their workforce.

Recall the eight demands issued by Cabin Creek miners that became the centerpiece of the first Mine War: union recognition, free speech and assembly on company property, a competitive market for supplies, an end to blacklisting and cribbing, installation of scales at all mines with accountable check-weight men, and a procedure for mutually-determined docking penalties. A wage increase is nowhere to be found. Indeed, every government report issued over the course of the Mine Wars identified issues of fundamental fairness and social dignity as the causes of violence in southern West Virginia. This provides evidence for the claim that “the Marxist emphasis on exploitation as the basic point around which classes rally carries an unduly economistic prejudice, obscuring the more-fundamental importance of social institutions, culture, social status and dignity,” along with the idea that “it is the degradation or deprivation of these bases of social-communal self-respect that we should expect to inspire revolutionary collective action.”

- Which mechanisms of the American system does the ruling class rely on in revolutionary situations, and how can revolutionary subjects effectively respond?

It will also be observed that the operators’ most-effective weapons in the Mine Wars were the unilateral rather than deliberative varieties state power. This is plausibly a result of the facts that executive powers are best suited to exigent circumstances, judicial powers are relatively unaccountable, and greater investments of time and capital are required to influence multi-member deliberative bodies. Even so, the implications for revolutionary situations are of interest. First, the Mine Wars demonstrate the impotence of legislative bodies for enforcing the gains which collectivities successfully extract from them: the operators continued to use the scrip system despite its illegality, blatantly employed thousands of private Baldwin-Felts agents for years after the practice was outlawed, and refused to pay wages guaranteed by the Lever Act until the Justice Department intervened. And the operators were further able to obtain wide-ranging judicial injunctions that limited the UMWA’s ability to mobilize in support of their legal rights.

The logical conclusion is that revolutionary collectivities would do well to participate in and attempt to influence the coercive apparatuses of the state. The UMWA’s efforts to elect pro-union sheriffs in the interwar period paid dividends by denying the operators protection for imported strikebreakers, while the extensive number of miners who participated in the American Expeditionary Force both improved the quality of arms available to them and prevented significant violence between federal and UMWA forces; in fact, “during the entire [federal] deployment” of the second Mine War, “none of the [UWMA] casualties were inflicted by federal forces” and “no violent incidents by miners against federal troops were reported.”[52] Greater investment by the UMWA in the unusually-powerful American judiciary might have further constrained the operators’ ability to resist union agitation.

A final dominant feature of the West Virginia Mine Wars that appears to fit nowhere in the literature on revolutions was the central importance of land ownership. Despite their limited area, those portions of southern West Virginia not owned by the coal operators were valuable respites for miners and unionists. UMWA organizers often delivered speeches standing on railroad platforms or ankle-deep in town waterways to avoid arrest by company agents, and the Union’s quick decisions to rent land in Holly Grove and Lick Creek at the outset of each Mine War provided members a meager but local residency beyond the operators’ plausibly-legitimate purview from which to conduct the strike.

Although property titles are no great weapon under circumstances of insurrection or martial law, it is undoubtedly true that the operators’ extensive land ownership was a great burden to the UMWA members, whether on strike or not. The miners themselves effectively utilized insurgent tactics which relied on their deep knowledge of the hills surrounding the well-guarded camps, but their lack of legal title to any useable property in southern West Virginia made them easy targets of surprise raids where they congregated and helpless victims of arbitrary violence elsewhere.

IV. Final Words

The West Virginia Mine Wars offer several insights into how the American constitutional system responds to revolutionary collective action. First, state governments demonstrate very little autonomy from their localized ruling class due to competition with other states for resources. The federal government’s nationwide responsibilities require a more evenhanded approach to insurgent collectivities due to diffuse resource extraction interests and broader concerns for social order. Second, there is evidence suggesting the superiority of an approach to class formation centered on shared experiences and the degradation of the social-communal bases of self-respect, implying that class interests at the root of revolutionary collective action rely less on economic exploitation and material want-satisfaction than Marxist theories contend. Third, influence over the unilateral and coercive apparatuses of American state power are of crucial importance in revolutionary situations, and the pronouncements of legislative bodies comparatively irrelevant. Finally, control of land prior to the outbreak of revolutionary violence appears to condition the ability of contending groups to press their claims and resist state repression.

The conclusions of one case study offer little more than starting points for further investigation, but the West Virginia Mine Wars, the largest insurrections in American history behind the Civil War, offer fertile ground for exploration of the unique dynamics of the American constitutional system in response to revolutionary collective action. Although the miners who fought on the hills of Kanawha County and the slopes of Blair Mountain failed to destroy the regimes they challenged, their story is a key chapter in the history of revolutions in the United States and worldwide.

Solidarity Forever.

[1] Zagorin, Perez. “Theories of Revolution in Contemporary History.” Political Science Quarterly 88, no. 1 (March 1973): 28-29, quoted in Hobsbawm, E. J. “Revolution.” In Revolution in History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

[2]Lipset, Seymour Martin. American Exceptionalism: A Double-Edged Sword. New York: Norton, 1996. Pg. 18.

[3] Hobsbawm, ibid., 7.

[4] Schattschneider, E. E. The Semi-Sovereign People. New York: Holt, Reinhart and Winston, 1960. Pg. 71.

[5] Hobsbawm, ibid., 5.

[6] Skocpol, Theda. States and Social Revolutions. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. Pg. 3, 5.

[7] Lieuwen, Edwin. Arms and Politics in Latin America. New York: Praeger, 1961. Pg. 21.

[8] Skocpol, id.

[9] Hobsbawm, ibid., 12, 19-20. See also Piven, Francis Fox, and Richard A. Cloward. Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail. Vintage. New York, NY: Random House, 1979. Pg. 7.

[10] Zagorin, id; Hobsbawm, ibid., 19; McAdam, Doug. Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970. Paperback. London: University of Chicago Press, 1985. Pg. 40-43; Tilly, Charles. “Does Modernization Breed Revolution?” Comparative Politics 5, no. 3 (April 1973): 425–47. Pg. 427.

[11] Tilly, Charles. From Mobilization to Revolution. First Edition. New York: Random House, 1978. Pg. 190-91. A version of this position was first articulated by Leon Trotsky. See also Piven and Cloward, ibid., pg. 4, discussion of ‘protest consciousness’.

[12] Skocpol, ibid., 11.

[13] Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. The Marx-Engels Reader. Edited by Robert C. Tucker. 2nd ed. New York: Norton, 1978. Preface to The Critique of Political Economy pg. 4-5.

[14] Id.

[15] Ibid., Manifesto of the Communist Party, 477-78.

[16] Gurr, ibid., 13.

[17] Ibid., 9.

[18] Skocpol, ibid., 10. Tilly 1978, ibid., 208.

[19] Johnson, ibid., 12, 9.

[20] Ibid., 16-17, 6-8.

[21] Ibid., 12.

[22] McAdam, Doug. Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970. Paperback. London: University of Chicago Press, 1985. Pg.11.

[23] Tilly 1978, ibid., 219; Arendt, ibid., 18-19.

[24] Tilly, 1978; McAdam, 1985. McAdam seeks to distinguish his theory from Tilly’s resource mobilization model by claiming it “grants too much importance to elite institutions [and] too little to the aggrieved population.” 21-29. I am not persuaded, however, by McAdam’s effort to distinguish the “certain indigenous resources facilitative of organized social protest” from the organizational resources Tilly discusses, which by no means exclude non-elite organizational capacity from importance, if not overwhelming influence. 30. The principal addition of McAdam’s theory is a protracted discussion of “political opportunity structures,” 40-43, which is a welcome addition to Tilly’s discussion of resource mobilization.

[25] McAdam, ibid., 39.

[26] Tilly 1973, ibid., 436. Skocpol, ibid., 24.

[27] Rudé, George. The Crowd in the French Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

[28] McDaniel, James Frank. “Political Assassination and Mass Execution: Terrorism in Revolutionary Russia, 1878-1938.” Doctor of History, The University of Michigan, 1976.

[29] Hobsbawm, ibid., 19, for Lenin’s use of the term. See also Marx and Engels, ibid., 4-5.

[30] Skocpol, ibid., 17.

[31] Id.

[32] Attributed to Wendell Phillips by Skocpol, id.

[33] Lenin, Vladimir Illyich. Lenin, Collected Works. Edited by Julius Katzer. Vol. 21: August 1914-December 1915. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1964. “The Collapse of the Second International.”

[34] Skocpol, ibid., 18.

[35] McAdam, ibid., 41.

[36] Schwartz, Michael. Radical Protest and Social Structure: The Southern Farmers’ Alliance and Cotton Tenancy, 1880-1890. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988. Pg. 172-73.

[37] Id., emphasis removed.

[38] Skocpol, ibid., 13. See also Piven and Cloward, Marx and Engels, Lenin, supra.

[39] Weber, Max. From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology. Translated by H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills. Oxfordshire: Routledge, 1948. Pg. 183, 193: “Class, Status, Party”; McAdam, ibid., 37.

[40] Polanyi, Karl. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. 2nd Paperback. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2001. Pg. 160. Emphasis mine.

[41] Id.

[42] Thompson, E. P. The Making of the English Working Class. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 2013. Pg. 8-12.

[43] This task is also taken up by Tilly in his discussion of the impotence of agitated yet under-resourced masses. Tilly 1978, ibid., 208. See also Davies’ theory of the “J Curve” Davies, James C. “Towards a Theory of Revolution.” American Sociological Review 27, no. 1 (February 1962): 5–19. Pg. 6.

[44] Calhoun, Craig. The Roots of Radicalism: Tradition, the Public Sphere, and Early Nineteenth-Century Social Movements. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

[45] Skocpol, ibid., 29.

[46] Ibid., 30.

[47] Brecher, Jeremy. Strike! San Francisco: Straight Arrow Books, 1972. Pg. 240. Quoted in Skocpol, ibid., 17.

[48] Hobsbawm, ibid., 13-14.

[49] Id. Parenthesis omitted.

[50] Ibid., 305.

[51] Ibid., 100.

[52] Laurie, id.